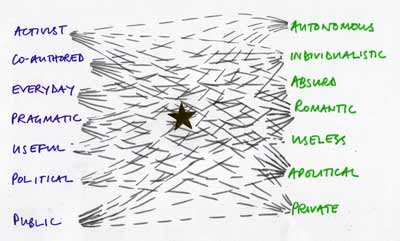

I have come across three different explanations of socially engaged art, all of which use four steps in their analyses. These are: Suzanne Lacy’s four positions of the artist; Mark Hutchinson's four stages of public art based on the dialectic of Roy Bhaskar and Declan McGonagle’s four dimensions of art. I have started to compare these models as each step seems to share something in common. Each description also implies that the fourth stage is the ultimate, ideal stage to work towards, which I would like to analyse further. The drawing above is a very basic breakdown of the different ways of working or defining socially engaged art. I would argue that most definitions would describe socially engaged art as being somewhere in the middle of this scale, but this is something I want to test through my research.

The reference for the three texts are:

Lacy, S., 1994. Debated Territory: Toward a Critical Language for Public

Art. In S. Lacy, ed. Mapping the Terrain. Seattle: Bay Press, 1994.

Hutchinson, M., 2002. Four Stages of Public Art. Third Text, Vol. 16, Issue

4. p.329-438.

McGonagle, D., 2007. Forward. In D. Butler and V. Reiss, eds., Art of Negotiation.

Manchester: Cornerhouse, 1997, p. 6-–9.

Stage One:

This activity prioritises the artist’s voice and leans towards the individualistic

side of the scale. Characteristics of this stage include reveling (rather

than critiquing) the artist’s role as outsider to a community and assuming

and relying on this privileged status in order to make one’s own work.

For Lacy, this first stage is described as ‘Artist as Experiencer’ where

‘the artist, like a subjective anthropologist, enters the territory of the

Other and presents observations on people and places through a report of

her own interiority. In this way the artist becomes a conduit for the experiences

of others, and the work a metaphor for relationship.’

For Hutchinson, we are at a stage of ‘non-unity, difference or alterity’.

He also describes this as ‘an anthropologist’s descent upon an exotic community…What

such an anthropologist would not observe or analyse would be his or her

own presence: the way he or she formed relationships with, affected, and

was affected by, the community in question.’ For Hutchinson, this is ‘un-self-reflexive’

where the production of the art is imposed on the context and viewers.

McGonagle sees the first stage as a selfish model – ‘a model of self in

the studio, value lies in the uniqueness rather than the commonality of

the artist’s experience – a model of separateness and often eccentricity,

of silence in the sociopolitical space and celebrated, admired and rewarded

as if fulfilling the only legitimate role of the artist.’

So we see here that a priority for the artist is researching and compiling

material about a given community. Such ‘separateness’, ‘selfishness’ and

‘non-unity’ in art could be seen as an arrogant position but could also

be understood as a strategy to undermine the expectations of the commission.

By revelling in the boondoggling nature of the futile act, an art project

could counteract the expectations of productivity placed on it by funding.

Richard Sennett describes ‘craftsmanship’ as the ‘desire to do something

for it’s own sake…the new order does not and cannot satisfy this desire…getting

something right, even though it may get you nothing is the spirit of true

craftsmanship…and only that kind of disinterested commitment…can lift people

up emotionally, otherwise, they succumb in the struggle to survive.’ By

taking a stance as distant observer, the artist is able ‘shock us out of

this perceptual complacency, to force us to see the world anew…[lifting]

the viewers outside of the familiar boundaries of a common language, existing

modes of representation and even their own sense of self’ (Kester, 2004).

The idea of the art process bringing some transcendent qualities can be

seen along the sliding scale but it is in this phase that it is most potent,

to the extent that some think the more removed from the everyday (the higher

up in the garret; the furthest towards the autonomous side of the scale)

the more possible it is to be subversive. Marcuse held this view:

‘Art is “art for art’s sake” in as much as the aesthetic form reveals tabooed

and repressed dimensions of reality…[art] shatters every day experience

and participates in a different reality…expresses a consciousness of crises:

a pleasure in decay, in destruction, in beauty of evil, a celebration of

the asocial, of the anomic – the secret rebellion of the bourgeois against

his own class’ (Marcuse, 1979).

Indeed, this rejection and distancing from the everyday is a repost to the

commonly adopted phrase in current social and cultural plans and policies:

the use of art. What if it is presented as having no use? Pointlessness

and uselessness could be a strategy of resistance in a society that demands

productivity, outcomes and quantifiable results. One of the loudest criticisms

of this current situation lambastes the instrumentalisation of culture and

calls for the reclamation and recognition of artistic autonomy. In their

recent essay, ‘Championing Artistic Autonomy’, the independent organisation,

The Manifesto Club, for example, argue for artistic autonomy from ‘physical,

political and financial restraints’ in order for the artist to ‘realise

a creative vision’ (The Manifesto Club, 2006). This argument falls neatly

into our autonomous side of the scale without question. The further away

we move from this position on the scale towards the everyday, the more we

begin to question the very notion of autonomy and with it the impossibility

of championing it.

Stage Two:

In this stage a process of self-reflection begins and the notion of autonomy

is questioned but the artist’s role is never the less affirmed in the process.

Participation and collaboration are attempted for the artist to make their

own work without relinquishing authorial control to those participants.

For Lacy this stage is the ‘Artist as Reporter’, as the artist gathers information

and makes it available to others. For Hutchinson it is about a process of

‘realisation and undoing of absences, lack, silences…The relationship between

subject and object becomes visible and agency becomes reciprocal’. He goes

on to say how at this stage there is a ‘negation of the idea of art’s detachment

from everything else. Some art hopes to adopt the culture or meanings of

a chosen public, without relinquishing the agency of the artist in the making

of the art’. There is a potential silencing of the subjects rather than

giving them a voice. In this process the public ‘appropriate existing public

art in a way utterly unintended by the authors of the work’. For McGonagle

there is also an acknowledgement of the ‘other’ and the artist’s intention

to communicate with this other.

This stage demonstrates a kind of schizophrenia towards responsibility,

which sometimes lies with the integrity of the work and at others with the

‘subjects’ or ‘community’ that the artist/anthropologist is ‘working with’.

Martha Rosler refers to this:

‘Anthropologist Jay Ruby believes that only self-reflexive documentary –

giving the camera to those represented – evades authoritarian distortion.

Others wish to interpret all representations as fictions. I disagree with

all these totalized criticisms’ (Rosler, 1994).

There are many histories of artists opening up their work to involve participants

throughout the 20th Century from the use of people as subjects in the making

of the artists work, to the handing over of artists’ initiatives to individuals

who go on to author the work as their own. Many of the projects that are

considered socially engaged embody a variety of types of participation (maybe

at different times of the project – at times the project may be more participant

than artist led). During stage two, participation in an art project does

not automatically result in the politicisation and activation of the participant.

Walter Benjamin in his essay, ‘The Author as Producer’ of 1934 describes

a notion of production, ‘which is able first to induce other producers to

produce, and second to put an improved apparatus at their disposal. And

this apparatus is better the more consumers it is able to turn into producers,

- that is, readers or spectators into collaborators.’

This second stage does not go that far as it tends to privilege the artist’s

own work and is reliant on their status as artist, although Benjamin’s call

for turning consumers into producers would perhaps ring true to many practicing

artists today as something that inspires them to develop projects, create

platforms and facilitate collective production. It could also refer to New

Labour policies of social inclusion and the rising trend of corporate social

responsibility through which much socially engaged art is funded. This top-down

process of empowerment, however, has been heavily criticised by the communities

of ‘consumers’ themselves, as being patronising and vacuous. Through the

veil of social inclusion (often delivered through community consultation

and socially engaged or public art) one witnesses or experiences the realities

of regeneration such as increased control and privatisation of public space

and rising house prices.

‘Daily life and its ambiguity, simultaneously effect and cause, conceal

these relations between parents and children, men and women, bosses and

workers, governors and governed. For it’s part, critical knowledge removes

the screen and unveils the meaning of metaphors’ (Lefebvre, 1947). One could

interpret this ‘critical knowledge’ as socially engaged art. During stage

two, the screen may be removed but only for the artist’s benefit; the ‘critical

knowledge’ may not extent to other (non-artists) involved.

Stage Three:

This stage goes further in analysing and negotiating with the systems and

structures that support the artistic process. For Lacy, the artist becomes

an analyst: ‘As artists begin to analyse social situations through their

art, they assume for themselves skills more commonly associated with social

scientists, investigative journalists and philosophers’. Hutchinson’s third

stage involves negotiations between the artist and other people in the process

of production and a reciprocal relationship begins between subjects. McGonagle’s

third dimension takes the artist beyond the gallery context and into public

space contexts, ‘usually based on negotiation with forces which own or control

public space rather than those who use it’.

The question is, to what extent does negotiation become co-option and what

are the issues with this? Owen Kelly in 1984 describes the problem with

the development of a professionalised, fully funded community arts practice:

‘Community artists are increasingly told what to do, and how to do it, by

people whose motivations often directly contradict the alleged aims of the

community arts movement. We have become foot soldiers in our own movement,

answerable to officers in funding agencies and local government recreation

departments…[leading to the] collapse of the community arts movement into

the waiting arms of the state’ (Kelly, 1984). The third stage acknowledges

its part in a bigger system but to what extent does ‘embedding radical creative

practice’ (as promoted by public art agency General Public Agency, for example)

decrease art’s ability to critique the process it is a part of?

‘By embedding radical creative practice into the decision-making and delivery

process, truly imaginative, innovative and tailor-made solutions become

possible due to the more lateral thinking and skills available to decision-makers’

(Meissen & Basar, 2006: 86).

Marcuse does not think complete assimilation into the system is a good idea:

‘The strength of art lies in its otherness, its capacity for ready assimilation.

If art comes too close to reality, if it strives too hard to be comprehensible,

accessible across all boundaries it can no longer negate the world…Art should

not help people become assimilated in the existent society but at each turn

challenge the assumptions of that society.’(Becker, 1994: 181)

A process of revealing and understanding the politics of production is applied

in practice by recognising and responding to ‘failures’. Another tactic

used by artists is to engage those involved in the decision-making processes

of the commissioning of art and the development of real estate as participants

in the work itself. This way it is possible to question the values placed

on art with a wider community of people allowing these values to be disrupted

and challenged not just by artists but also by those supporting art and

getting involved in its production. Can the project at times be focused

too much on negotiating and providing platforms for the ‘decision-makers’

rather than the communities who these decisions will affect?

Stage Four:

This final stage is where the art is open to interpretation by the different

people involved. ‘Artistic control’ is relinquished and the emphasis is

on agency and transformation. Lacy describes this as when the artist turns

activist: ‘art making is contextualised within local, national, and global

situations, and the audience becomes an active participant…Artists reposition

themselves as citizen-activists. Artist-activists question the primacy of

separation as an artistic stance and undertake the consensual production

of meaning with the public’. Hutchinson’s fourth stage involves agency and

practices of transformation. ‘Art would be an art that changes what art

it…Public art that potentially transforms itself; transforms its publics;

allows itself to be transformed by its publics; and allows these relationships

and definitions to be transformed too.’ McGonagle’s selfless fourth stage

‘houses other models in a field of negotiation rather than of fixed positions,

reconnected to a social continuum and also reconnecting arts aesthetic and

ethical responsibilities.’

This fourth stage of socially engaged art is perhaps the preferred method

of our three ‘model-makers’ as the most critical and effective way of working.

Grant Kester points out, however, that such ‘dialogical works’ are often

not considered as serious, critical art: ‘dialogical works are criticized

for being unaesthetic or are attacked for needlessly suppressing visual

gratification. Because the critic gains no sensory stimulation or fails

to find the work visually engaging, it is dismissed as failed art’ (Kester,

2004: 10-11).

Due to the specifics of this economic situation, the critical aspect of

a socially engaged art practice shifts a gear from direct action (to activate

and empower individuals) to question the very nature and meaning of a socially

inclusive agenda. Rather than becoming the vehicle through which urban developers

can market their social responsibility, for example, such projects have

the potential to demand a more thorough, democratic involvement of different

people in the inevitable development of the ‘masterplanned community’. This

marks a shift in the focus of the critique to a questioning of the means

of production thereby unravelling the reason why the money is there for

the socially engaged art in the first instance. The critique now involves

a probing of the motivations of corporations and governments to empower

and make producers of us all and questions the artists’ role and position

in carrying out the objectives of an art that could be interpreted as a

waste of time and money (in other words, a complete ‘boondoggle’).

Does the fourth model which is all about the experience of ‘getting involved’

and ‘participating’ mean it will have a transformative effect? How can an

art that aims to ‘subvert’ the status quo be effective when those involved

are unable or unwilling to change? Who, essentially, are the artists working

for? How is the map, the walk, the technology used, adopted and manipulated?

There have been discussions locally about the emotion mapping technology

being used to map the content of local meetings in order to adopt a visual

mode of communicating key issues or concern to other groups and decision-makers.

There are also plans to develop the project further in collaboration with

a local artist so that the project is embedded in the local context and

has the potential to become even more locally relevant. The future use of

the technology and the maps will determine to what extent the users will

become producers.